I wrote this originally in November of 2008, right after Barack Obama had been elected President of the United States. There was a lot of speculation at that time about whether or not the Christian Church in America was going to face massive persecution under his administration.

In retrospect, eight years later, I see that the Church wasn’t persecuted. Inconvenienced, adversarial, unpleasant was more like it.

I wrote what follows then as my attempt to inject some perspective into the situation. I’m not sure I succeeded, but I tried my best.

It’s now 2020 and I’m sensing that the Church may be on the brink of a different kind of persecution, one where we are no longer the American majority, our worldly wealth has been stripped, and the dynamics of the persecution will be altogether different than what we thought it was going to be.

The words written in 2008 follow:

“While we seek mirth and beauty and music light and gay

There are frail forms fainting at the door.

Though their voices are silent, their pleading looks will say.

Oh, hard times come again no more.

‘Tis the song, the sigh of the weary.

Hard times, hard times, come again no more.

Many days you have lingered all around my cabin door.

Oh, hard times, come again no more.”

– Bob Dylan – “Hard Times” (Stephen Foster) – 1992

The election is over. In keeping with American tradition, rampant speculation has become the order of the day. Will President Obama govern from the left? The center? Will America become a socialist state? Will the Democrats start sending out the goon squads to squelch any signs of dissent? What will Obama’s agenda be? Not to be outdone, some Evangelicals are speculating far into the future. In a letter that’s making the internet rounds, a future Christian, circa 2012, laments the impact Barack Obama’s presidency has had on people of faith, particularly Evangelical Christians. A few samples follow”

“I can hardly sing “The Star Spangled Banner” any more. When I hear the words,

“O say, does that star spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?”

I get tears in my eyes and a lump in my throat. Now in October of 2012, after seeing what has happened in the last four years, I don’t think I can still answer, “Yes,” to that question. We are not “the land of the free and the home of the brave.” Many of our freedoms have been taken away by a liberal Supreme Court and a Democratic majority in both the House and the Senate, and hardly any brave citizen dares to resist the new government policies any more.”

“Personally, I don’t know how we are going to get through tomorrow, for these are difficult times. But my faith in the Lord remains strong.”

Heart wrenching, wouldn’t you say? Well, be strong my brother…be strong!

I don’t know whether the author of the letter was prompted by some special prophetic insight or was projecting his/her fears for the future. I profess no special insight into the future, nor do I harbor an overwhelming sense of dread. I can say that as I walked the dogs this morning the sun still rose in the east. I can also say that my wife, Nancy, still loves me. She even told me so before she left for Topeka at 6:30. It’s now about 11:00 A.M. and no one from the thought police has descended on my home to confiscate my Bible. I’d even read from it a couple of hours ago, from Paul’s second letter to the Church in Corinth, in which the apostle provides some valuable insight into what one of his average days looked like.

“Are they servants of Christ? I know I sound like a madman, but I have served him far more! I have worked harder, been put in prison more often, been whipped times without number, and faced death again and again. Five different times the Jewish leaders gave me thirty-nine lashes. Three times I was beaten with rods. Once I was stoned. Three times I was shipwrecked. Once I spent a whole night and a day adrift at sea. I have traveled on many long journeys. I have faced danger from rivers and from robbers. I have faced danger from my own people, the Jews, as well as from the Gentiles. I have faced danger in the cities, in the deserts, and on the seas. And I have faced danger from men who claim to be believers but are not. I have worked hard and long, enduring many sleepless nights. I have been hungry and thirsty and have often gone without food. I have shivered in the cold, without enough clothing to keep me warm. Then, besides all this, I have the daily burden of my concern for all the churches. Who is weak without my feeling that weakness? Who is led astray, and I do not burn with anger? If I must boast, I would rather boast about the things that show how weak I am.”

Who really had the tougher road to hoe, the first century apostle or our hypothetical Christian in 2012?

Do we really believe we’re being persecuted? Can we really convince ourselves that a three percent hike in taxes rises to the level of being beaten with rods? If our hypothetical Christian is to be believed, apparently so.

Well, I guess if our future Christian can engage in flights of fancy, I can too.

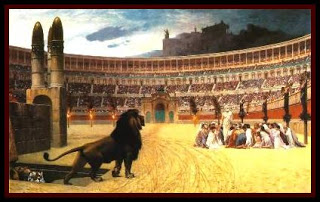

I wonder what things might look like in an imaginary meeting room for martyrs in heaven designed so that new arrivals can get a taste of what things are like just beyond the pearly gates. The year is 2009, a short time after the election of Barack Obama, liberal Democrat. Several new American arrivals have been ushered into the meeting room. There, seated before them, are men and women dressed in garb from the first century all the way to the 21st. They are an amalgamation of nations, ethnicities, races, and ages. There are even children.

Once the new arrivals are seated, a short, balding man comes to the podium. He clears his throat and announces, “It’s good to meet you new arrivals. Make yourselves at home. I’m Paul. I’m told I’ve been here a couple of thousand years now, but, to be honest with you, I’ve lost all track of time.” After a moment or two of polite laughter, Paul goes on. “I’m going to begin by telling you how I got here, then letting a few others describe their entry. Once they’re done, we’ll open the floor to you new arrivals to acquaint us with the circumstances surrounding their arrivals. Does that seem good to you all?” Everyone nods in agreement. “Good, then. I’m Paul. I spent a good part of my life getting whacked around like a piñata for professing my faith in Jesus. Why, once I got thrown on a pile of garbage and left for dead. The Romans finally got me and lopped off my head.” The new arrivals begin to feel lumps forming in their throats. Paul goes on. “I’m going to ask young Mary to describe her circumstances for you.” A young woman, circa fifteenth century, stands. “Hi, I’m Mary. I lived a quiet life of faith and contemplation in Spain until Torquemada got a hold of me and thousands of others like me. He had me ripped from limb to limb and here I am.” The new arrivals feel the lumps in their throats getting bigger. Paul then introduces a couple of young children, a boy and a girl. “We were thrown to wild beasts.” The lumps in the throats now seem to inhibit the breathing of the new arrivals. But, on and on it goes. One martyr recalls being covered with grease and lit up as a torch to light the Appian Way for Nero. Another describes being burned at the stake for reading an unauthorized translation of the Bible in the 16th century. A recent arrival, a 20th century North Korean woman, recounts how she and hundreds of her fellow Christian villagers were run over and flattened by tanks and bulldozers. Paul caps it all off by reminding the new arrivals that there is Someone with nail pierced hands in heaven who’s suffered more than all those assembled.

By now the new arrivals can hardly breathe. Paul encourages them to calm down so that they can tell their tales of woe. It takes a few minutes, but the testimonies begin. A fortyish man, dressed in an Armani suit, describes, in lurid detail, being taxed to death. “Early in 2008 my marginal rate was 36%. By 2009 it was 39%. The minute the first deduction hit my paycheck I had a heart attack and keeled over, dead.” The testimony is greeted with stunned silence. Next, a man dressed in bib overalls, apparently a farmer, defiantly declares, “I tried my best to live life under “librull” rule, but I could only hold out for a few months thinking of life without a gun before I blew my brains out. Yup, the librulls got me.” Icy silence follows. A woman, dressed to the nines, Ann Taylor, I think, tearfully describes how the interruption in her life of conspicuous consumption led to her untimely death. “Why, money was so tight I could only shop at Bloomingdale’s three or four times a week. I died of a broken heart.” By now, Paul and the others have heard enough. “Do you mean to tell me that you believe that a three percent jump in taxes, a liberal Democrat, and a shortage of money for high-end consumer goods got you here?” Knowing now that they have no good reason to be in a room full of martyrs, the lumps in the throats of the new arrivals now appear to be the size of softballs. They are gasping for breath. All they have to say, in muffled tones, at this point is, “Get us outta’ here, things are feeling very uncomfortable.”

I don’t know what things are going to be like in this country four years from now, but I can’t work myself into a state of hysteria because of a change in political administrations. I just can’t do it. I don’t believe that Barack Obama is the end of the world. I’m no candidate for martyrdom, but neither am I in any frame of mind to embrace a persecution complex for what seem to me to be trivial reasons. History has shown that we Christians can be a pretty hardy lot if we put our minds and hearts to it. Why, on our collective paths to heaven we’ve been burned at the stake, bludgeoned, torn into pieces, flattened like pancakes, sawn in two, thrown to wild beasts, drowned, beheaded, hanged by the neck, drawn and quartered, cooked in boiling oil, suffocated, and stretched on the rack. Knowing this, I find it less than amusing to think that having a liberal Democrat and his family occupying the White House will undo our faith in Jesus Christ. I’d like to think our faith is made of better stuff than that.